|

The Ennominae are the largest subfamily of the Geometridae. In the

Bornean fauna just under half the species are ennomines. The traditionally

diagnostic feature for the subfamily is loss (or reduction to a fold) of vein M2

on the hindwing. No other features have been located that are shared by all

major tribal groupings within the Ennominae, so the monophyly of the group is

only weakly supported.

The group as a whole has a wide ecological range, occurring in diversity

at all except very high latitudes and, in the tropics, altitudes. In Borneo,

Sulawesi and Seram, ennomines show their greatest diversity in the lower montane

zone (Holloway, 1984a, 1993; Holloway, Robinson & Tuck, 1990).

Some ennomines show specificity to lowland forest types, such as heath

forest, alluvial forest or mangrove. The subfamily also includes several species

that appear to fly predominantly in the forest understorey. Ennominae are

therefore highly suitable as an environmental indicator group except for poor

representation in open habitats (Holloway, 1984a, 1985; Holloway &

Barlow, 1992).

An attempt is made here to define tribal groupings and suggest a higher

classification for the subfamily, though this is based primarily on groups

represented in S.E. Asia. Host-plant specialism is also reviewed in relation to

this classification.

Family-group names

The attempt to assess the higher classification of the Ennominae and to

assign genera to tribal groupings necessitated an investigation of prior usage

of family- group names. This in turn led to the accumulation of about 150

family-group names used for the Geometridae and some indication of when these

names first appeared. For the subfamilies Oenochrominae, Geometrinae, and

Sterrhinae the listings of Prout (1912, 1913, 1934-5) provide a foundation,

though a number of family-group names have been erected subsequently, e.g. in

the Geometrinae by Inoue (1961) and Ferguson (1969). Prout did not publish lists

for the Larentiinae and Ennominae.

In the Code of Zoological Nomenclature, rules of priority for

family-group names tend to apply, but somewhat less strictly than for

genus-group and species-group names. After 1960, family-group names based on

junior generic synonyms may not be replaced by a new name based on the senior

generic synonym, but can be replaced by extant family group names based on

senior generic synonyms or by senior family group names based on other genera

within the concept of the reclassification. Before 1961, such replacements can

stand if the replacement name has won general acceptance. Thus Bistonini should

probably stand in relation to the older Amphidasini and Hyberniini (replaced by

Erannini), though Seven (1991) uses Amphidasini (see list below for details).

Reinstatement of the genus Macaria Curtis from synonymy with Semiothisa

Hübner strengthens the case for preferring Macariini to Semiothisini (as

does Seven), as Macariini is the senior name.

It became apparent during this investigation that reclassification of

the Sterrhinae, a subfamily name indicated by Fletcher (1979) to be preferred,

will probably lead to even greater changes to family-group names. Indeed,

Mikkola et al. (1985) and Seven (1991) have reverted to using

Scopulinae for this subfamily based on the oldest name (Scopulites, Duponchel

(1845)). The situation is therefore reviewed briefly here to exemplify

the problems that can be encountered. Revision of the classification may show

that the group is polyphyletic rather than monophyletic: even if monophyletic,

it may contain seven groupings:

Scopulini (= Acidaliini Duponchel (1845) based on a junior

homonym of a genus-group name outside the Lepidoptera). Scopula and

allied genera;

Cyclophorini Moore (1887) (= Zonosomini White (1876, Scot. Nat. 3:

361), reintroduced probably on priority grounds by Seven (1991) but Cyclophora

is a senior objective synonym of Zonosoma; Cosymbiini Prout (1911, Tr.

City Lond. ent. soc. 20: 23)), which traces back to the Cyclophorae

of Hübner. The name Ephyrini of Guenée (1857) is based on a junior homonym of

a genus group name outside Lepidoptera but was applied to the concept of

Cyclophorini. Another reason for preference of Zonosomini is the usage of the

family-group name Cyclophoridae in Mollusca, based on Cyclophorus Montfort.

The moth group includes genera with a distinctive girdle to the pupa (Holloway,

Bradley & Carter, 1987);

Idaeini Butler (1881) (= Sterrhini Meyrick (1892), a seniority that must

stand both on grounds of priority and because Sterrha Hübner is

currently treated as a junior subjective synonym of Idaea Treitschke);

Timandridi Stephens (1850) (= Calothysanini Herbulot (1962-3)). This

name is used by Hodges et al. (1983) and Seven (1991);

Rhodometrini Agenjo (1952);

Cyllopodini Warren (1895);

Rhodostrophini Prout (1934-5).

The family-group names (over 60) listed below have been located for

possible usage within the Ennominae. Invalid names, based on junior homonyms,

usually of genus-group names outside the Lepidoptera, are indicated by square

brackets.

The literature references given are only of those considered to indicate

both early usage and currency in modern literature. Whilst an attempt has been

made to ensure the earliest reference has been located, this cannot be taken as

categorical as the search was not exhaustive. The task is considerably

complicated by both past and present reluctance of authors to indicate authority

of the family-group names they use or to own up to new concepts.

However, the earliest dates located for names within Oenochrominae,

Geometrinae and Sterrhinae up to the Catalogus Lepidopterorum publications

of Prout (1912, 1913, 1934-5) were found to be the same as in Prout’s

lists. Many of Duponchel's names are attributed to Guenée, but represent the

first published occurrence.

ABRAXINI: Abraxinae Warren (1893); Swinhoe (1900), Hodges et al. (1983),

Seven (1991). (See Abraxini.) Conceptually replaced the unavailable

Zerenini, and see

also Pantherini (q.v.).

AMPHIDASINI: Amphidasites Duponchel (1845); Bruand (1846), Guenée

(1857). Amphidasis Treitschke is a junior objective synonym of Biston Leach

(Fletcher, 1979). Used for concept of Bistonini by Seven (1991). (See

Boarmiini.)

ANAGOGINI: Anagogini Forbes (1948); Hodges et al. (1983).

Subordinated here to Hypochrosini.

ANGERONINI: Angeronini Forbes (1948); Hodges et al. (1983).

Applicable to concept of Aspilatini (q.v.) as Aspitates and Angerona share

a costal ampullate process to the valve and other features of the male genitalia

(see McGuffin (1987)) and Higher Classification.

ASCOTINI: Ascotinae Warren (1893). Included in the strict concept of

Boarmiini of Sato (1984a).

[ASPILATINI]: Aspilatites Duponchel (1845); Bruand (1846). Based on a

misspelling of the genus-group name Aspitates Treitschke (see Fletcher

(1979)). The concept is currently included in Angeronini (q.v.).

AZELININI: Azelinini Forbes (1948); Hodges et al. (1983). Larval characters suggest a relationship to Nacophorini

(Heitzmann, 1985).

BAPTINI: Baptini Forbes (1948); Hodges et al. (1983) include the

older name Palyadini (q.v.) within their concept, but see discussion of Baptini.

BISTONINI:

Bistonidi Stephens (1850); Humphreys (1858-9), Hodges et al. (1983) but

see Amphidasini and Boarmiini, Biston

Leach.

BOARMIINI:

Boarmites Duponchel (1845); Bruand (1846), Stephens (1991). (See

Boarmiini.)

BRACCINI:

Braccinae Warren (1894). (See Boarmiini.)

BUPALINI:

Bupalini Herbulot (1962-3); Leraut (1980). Not investigated here, but the bifid

cremaster indicates relationship to the Boarmiini group of tribes.

CABERINI:

Caberites Duponchel (1845); Bruand (1846), Stephens (1850), Guenée (1857), Hodges

et al. (1983), Seven (1991). See also Deiliniini (q.v.), and concept may

also incorporate Erastriini and Catopyrrhini (q.v.). (See

Tribe Caberini).

CAMPAEINI:

Campaeini Forbes (1948); Hodges et al. (1983), Seven (1991). Metrocampini

(q.v.) is an older name but based on a junior objective synonym of Campaea Lamarck

(Fletcher, 1979).

CASSYMINI:

This volume. May embrace the N. American (Forbes, 1948) concept of Abraxini (See

Tribe Cassymini).

CATOPYRRHINI:

Catopyrrhinae Warren (1894). See Erastriini (q.v.) and Tribe

Caberini.

CHEIMATOBIINI:

Cheimatobiidi Tutt (1896). See Theriini (q.v.). Cheimatobia Stephens is a

junior objective synonym of Theria Hübner.

CINGILIINI:

Cingiliini Forbes (1948). Some usage in N. America but generally subordinated to

Ourapterygini (q.v., Forbes et al. (1983)). The relationship between the

two needs clarification; larval characters indicate a close

relationship with the Ennomini (Heitzmann, 1985).

CLEORINI:

Cleorites Duponchel (1845); Stephens (1850). Included in the strict

concept of Boarmiini of Sato (1984a).

COLOTOINI:

Colotoini Herbulot (1962-3); Seven (1991).

COMPSOPTERINI:

Compsopterini Herbulot (1962-3); Leraut (1980). See Ligiini, Pachycnemiini and

Prosopolophiini (q.v.). Status not investigated here. The type genus includes a

number of robust Palaearctic species.

CROCALLINI:

Crocallidi Tutt (1896). No current usage located.

DASYDIINI:

Dasydites Duponchel (1845); Stephens (1850), Tutt (1896). Based on a junior

objective synonym of Sciadia Hübner. Concept not investigated here.

DEILINIINI:

Deiliniinae Warren (1893). (See Tribe Caberini).

EMPLOCIINI:

Emplocidae Guenée (1857). Based on a Neotropical genus; not investigated here.

ENNOMINAE:

Ennomites Duponchel (1845); Bruand (1846), Guenée (1857), Hodges et al. (1982),

Seven (1991). See also Odopterini (q.v.) and Cingiliini.

EPIONINI: Epionidae Bruand (1846); Stephens (1850), Humphreys (1858-9).

EPIRRHANTHINI: Epirrhanthini Forbes (1948); Hodges et al. (1983).

Not investigated. McGuffin (1981) notes some similarities with Lithinini (q.v.).

A small N. American group.

ERANNINI: Eranniinae Tutt (1896); Dugdale (1961). See also Hyberniini

(q.v.). Hybernia Berthold is a junior objective synonym of Erannis Hübner

(Fletcher, 1979). Tutt included Eranniinae as a subfamily of Hyberniidae! Taxa

usually included in modern concepts of Bistonini/Amphidasini.

ERASTRIINI: Erastriae Hübner (1825); Erastridae Herrich-Schäffer

(1845); Stephens (1850). The original concept was applied to the acontiine

Noctuidae for a considerable time. Classification of the generic type species

(see Fletcher, 1979) leaves this family-group name applicable within the

Ennominae. See Cryptopyrrhini and Tribe Caberini.

EUBYJINI: Eubyjinae Warren (1893). Eubyja Hübner is based on a

species currently included in Biston Leach. See Amphidasini and Bistonini.

EUTOEINI: This volume; (See Eutoeini).

FERNALDELLINI: Fernaldellinae Hulst (1896) Based on a N. American genus

currently placed within the concept (Hodges et al. 1983) of the Macariini/ Semiothisini (q.v. and

see Macariini).

FIDONIINI: Fidonites Duponchel (1845); Bruand (1846), Stephens (1850),

Guenée (1857). Has been used to include Macariini/Semiothisini

subsequently (Packard, 1876) but is based on an unrelated S. European taxon. (See

Macariini). The name has not been used by Herbulot (1962-3) or Leraut (1980).

GNOPHINI: Gnophites Duponchel (1845); Bruand (1846), Stephens

(1850), Seven (1991). Not investigated in detail but probably subsumed by the

concept of Boarmiini in this volume.

GONODONTINI: Gonodontini Forbes (1948); Hodges et al. (1983).

Applied in the sense of Odontoperini (q.v.). Redefined in this volume (See

Gonodontini).

HYBERNIINI: Hibernites Duponchel (1845); Bruand (1846), Stephens (1850),

Guenée (1857). See Erannini. Falls within current concepts of Amphidasini/

Bistonini.

HYPOCHROSINI: Hypochrosidae Guenée (1857); Kirby (1897). See

Anagogini and (See Hypochrosini).

LACARIINI: Lacarini Orfila & Schajovskoy (1959). Associated with

Lithinini by these authors and Rindge (1986). (See

Lithinini).

[LIGIINI]: Ligidae Guenée (1857). Based on a junior homonym of a genus group name outside

Lepidoptera. See Compsopterini, Pachycnemiini and

Prosopolophini (q.v.).

LITHININI: Lithinini Forbes (1948); Hodges et al. (1983). (See

Lithinini).

MACARIINI:

Macaridae Guenée (1857); Moore (1887), Swinhoe (1900), Seven (1991). See

Semiothisini (q.v.), Fernaldellini and Macariini.

MELANCHROIINI:

Melanchroiinae Hulst (1896); Kirby (1897). Applicable to a small New World

group; not investigated here.

MELANOLOPHINI:

Melanolophini Forbes (1948); Hodges et al. (1983). A New World group that

probably falls within the broad concept of Boarmiini applied here.

METROCAMPINI:

Metrocampidae Tutt (1896). See Campaeini.

MILIONIINI:

Milioniini Inoue (1992) is the only reference so far located. In the absence of

a published definition, or mention before 1930, the name is not available. The

type genus falls within the concept of Boarmiini here (See

Boarmiini).

NACOPHORINI:

Nacophorini Forbes (1948); Hodges et al. (1983). A New World group

outlined by Rindge (1961). The tribe is possibly related to the Azelinini (see

above).

NEPHODIINI:

Nephodiinae Warren (1894). A Neotropical group not studied here.

OBEIDIINI:

Obeidiini Inoue (1992) is the only reference so far located. In the absence of a

published definition, or mention before 1930, the name is not available. The

type genus falls within the concept of Boarmiini here (See

Boarmiini

).

ODONTOPERINI:

Odontoperinae Tutt (1896). Fulfils the N. American concept of Gonodontini (see

above and (See Gonodontini).

[ODOPTERINI]:

Odopteridi Stephens (1850), Humphreys (1858-9). Odoptera Sodoffsky is an

unnecessary objective replacement name of Ennomos Treitschke. See

Ennominae.

ONYCHORINI:

Onychorini Herbulot (1962-3); Leraut (1980). Based on W. Palaearctic genus not

studied here.

OURAPTERYGINI:

Urapteridae Bruand (1846); Guenée (1857), Warren (1893), Hampson (1918;

preferred to Ennominae for subfamily, as based on the oldest genus-group name),

Forbes (1948; ?first spelling as Our- rather than Ur-), Hodges, et al. (1983).

See Cingiliini and Ourapterygini.

PACHYCNEMIINI:

Pachycnemiidae Kirby (1903); as replacement name for Ligidae. See above and also

Compsopterini and Prosopolophini.

PALYADINI:

Palyadae Guenée (1857); Moore (1887), Warren (1894), Hulst (1896), Kirby

(1897). Subordinated to Baptini in Hodges et al. (1983) but see Baptini.

Guenée's concept of this group is valid today if Eumelea Duncan is

excluded (M.J. Scoble, pers. comm.).

[PANTHERINI]:

Pantheridae Moore (1887), as replacement for Zerenini (q.v.) but Panthera Hübner

is a junior homonym of a genus-group name outside the Lepidoptera (Fletcher,

1979). (See Abraxini.)

PLUTODINI:

Plutodinae Warren (1894); Swinhoe (1900). (See

Plutodini).

PROSOPOLOPHINI:

Prosopolophinae Warren (1894); Swinhoe (1900). Proposed to replace Ligidae (see

above, and also Compsopterini and Pachycnemiini).

RUMIINI: Rumiinae

Tutt (1896). Based on Rumia Duponchel, a junior objective synonym of Opisthograptis

Hübner. No current usage located.

SCARDAMIINI:

Scardamiinae Warren (1894). (See

Scardamiini).

SELENIINI: Seleniidi

Tutt (1896). Probably best subsumed by Ennomini; (See

Introduction).

SELIDOSEMINI:

Selidosemidae Meyrick (1892); Warren (1893). Based on a European and N. African

genus not studied here. The concept of earlier authors probably coincides with

Boarmiini as treated here.

SEMIOTHISINI:

Semiothisinae Warren (1894); Hodges et al. (1983). See Macariini and

Fernaldellini.

SIONINI: Sionites

Duponchel (1845); Bruand (1946), Stephens (1850), Guenée (1857). Based

on a European species included in Gnophini by Herbulot (1962-3).

SPHACELODINI: Sphacelodini Forbes (1948); Hodges et al. (1983). A New World group not

investigated here.

THERIINI: Theriini

Herbulot (1962-3); Leraut (1980). See Cheimatobiini. This is based on a

Palaearctic genus that, from pupal cremastral characters, probably falls within

the broad concept of Boarmiini applied here.

THINOPTERYGINI:

This volume. (See Thinopterygini )

[ZERENINI]:

Zerenites Duponchel (1845); Bruand (1846), Stephens (1850), Guenée (1857). Based

on a junior homonym of a genus-group name outside the Lepidoptera. See Abraxini

and Pantherini.

The higher

classification of the Ennominae

An attempt has been

made in the systematic section to group Bornean genera of ennomines into tribes.

In some instances (e.g. Caberini, Baptini) it was possible to recognise a major

generic grouping defined by several characters, but association of this grouping

with the type genus of the tribe was more tenuous.

The absence as a

tubular vein or weakening of vein M2 in the hindwing currently defines the

subfamily. In this section potential groupings of tribes within it will be

assessed.

Forbes (1948)

divided N. American tribes on characters of the pupal cremaster: whether it was

apically bifid only (Group D of Mosher (1916)) or with more than two spines

(usually eight: four pairs). McGuffin (1981) suggested that the bifid condition

was the more primitive, reversing an earlier opinion which, on surveying

cremaster characters in Geometroidea generally, was probably correct: the bifid

condition is derived.

Data on geometroid pupae from Forbes, McGuffin, Mosher (1916), Sato

(1984a), Carter (1984), Khotko (1977) and the manuscript notes on the Indian

fauna by T.R.D. Bell indicate that possession of eight cremastral hooked shafts

is the commonest and more generally distributed condition seen in the

Cyclophorini, Naxa Walker amongst the Oenochrominae (?Orthostixini), the

majority of Geometrinae and Larentiinae, and also in the Drepanidae, Uraniidae

and Epiplemidae.

The bifid condition is not unique to the Ennominae but is much less

frequent elsewhere. It occurs in some, but not all, Scopulini where the

cremaster consists of two parallel shafts rather than divergent ones. The

Alsophilini have the cremaster bifid, almost T-shaped as does Operophtera (but

not Epirrita, where the 'T' is associated with two pairs of reduced

hooklets) of the larentiine tribe Operophterini (Packard, 1876; = Oporiniini of

Seven (1991)) (Carter, 1984). In the Eupitheciini all conditions occur from

eight shaftlets, through two strong ones and six weaker ones, to two shaftlets;

the Epiplemidae show a similar range of conditions. The bifid condition is seen

in some other larentiine genera such as Aplocera Stephens and Lithostege

Hübner. In the Archiearinae the cremaster resembles that of Alsophila (Mosher,

1916; Nakamura, 1987).

Hence it is probable that, within the Ennominae, the divergently bifid

cremaster represents a derived condition. It brings together the Boarmiini sensu

lato (See Boarmiini) with the

Macariini, Cassymini and Eutoeini. The inclusion

of Abraxini by Forbes rests on his examination of N. American genera he assigned

that tribe but which are probably better placed in Cassymini (See

Cassymini n.).

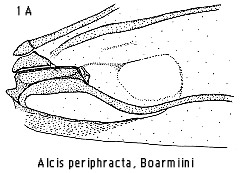

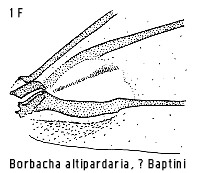

Adults

All the tribes with a bifid cremaster have the male forewing foveate in

a high proportion of genera, although the fovea is structurally different in

each (Fig 1). Occurrence of a forewing fovea is rare elsewhere in the Ennominae,

e.g. in Corymica Walker of the Hypochrosini and Borbacha Moore,

tentatively assigned here to the Baptini. Debauche (1937) defined a subgeneric

taxon in the Palyadini on presence of a fovea, somewhat as in Borbacha, but

with a spur from vein CuA as in the Macariini. Outside the Ennominae a fovea

occurs in Noreia venusta Warren, uniquely in a pantropical complex of

genera currently in the Oenochrominae that was identified by Holloway (1984b:

139). This complex must now be expanded to include the Indo-Australian genus Celerena

Walker as it shares the definitive features of the male abdomen. The

geometrine genus Dysphania Hübner also has a strong fovea, but again

structurally different from ennomine types.

Nevertheless, the frequency of the foveate condition supports the

relationship of these ennomine tribes suggested by the pupal character. A

further character that may serve to unite them is the presence of a cucullate

anterior apical portion of the valve that supports a concentration of the valve

setae; these setae extend more sparsely down the costal zone of the valve. In

the Macariini and Eutoeini this zone is separated from the sacculus as the

dorsal arm of the valve by a c!eavage that extends almost to the base of the

valve. In the Cassymini the valve is similarly cleft but the dorsal arm is

reduced to a slender process that usually only bears a few apical setae. In

other tribes the setae tend to be more generally and sparsely distributed over

the anterior of the valve lamina or, as in the Palyadini and a generic grouping

in the Baptini, concentrated elsewhere on the valve. However, not

all Boarmiini exhibit this cucullus.

The division of the valve may provide a synapomorphy to group the Cassymini, Eutoeini and

Macariini, but it is not clear whether the mode of

cleavage is homologous or homoplasious: it appears somewhat different in each

case.

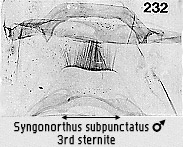

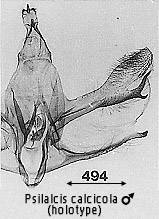

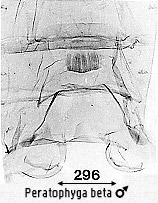

Another feature common to all four tribes is the presence in many genera

of a transverse comb of posteriorly directed setae on the male third abdominal

segment (e.g. Figs 232, 251, 296-8, 349, 369, 494). This appears often to be

correlated with the presence of a hair pencil sheathed within the hind tibia

(e.g. Rindge, 1983) and may serve as a means of distributing scent from that

pencil. But this feature is also seen in other tribes, e.g. for the Bornean

fauna: Abraxini, Gonodontini, Lithinini, Ourapterygini.

Setal ornamentation is seen elsewhere in the Geometridae but not in the

form of a transverse comb. In the Noreia/Celerena group of the

Oenochrominae mentioned earlier the setae occur in two robust patches arranged

symmetrically on either side of the mid-line, separated by a group of finer

setae forming together a roughly circular area (Celerena) or in two

sparser, more widely separated patches with no setae in between (Noreia Walker).

In the Geometrinae there is usually a diffuse patch on each side linked by a

region with sparser setae in between. These are more easily detached than in

Ennominae, except in Pingasa Moore and allied genera where they are more

robust.

In the Noreia group and Ozola Walker (Desmobathrini) in

the Oenochrominae and in the Geometrinae, occurrence of a tibial hair pencil is

frequent but the transverse comb arrangement of the sternal setae appears to be

unique to the Ennominae. The occurrence of a hair pencil/setal connection in

groups outside the subfamily makes it unclear whether the comb is a feature of

the Ennominae ground plan, and therefore its consistent absence in a tribe is a

derived feature, or whether it can be treated as a synapomorphy for the tribes

that possess it, i.e. grouping the Abraxini, Gonodontini, Lithinini and

Ourapterygini with the bifid cremaster complex of tribes.

Rindge (1983) treated presence of setal comb and hair pencil as

apomorphic states within his concept of the Nacophorini, a New World tribe with

some representation in Australia (McQuillan, 1981) that has variable pupal

cremastral ornamentation from two to eight shaftlets, and was assigned by Forbes

(1948) to his non-bifid group of tribes.

McQuillan (1985) revised the Australian ennomine genus Mnesampela Guest,

where the larvae have a full set of prolegs albeit with those on A3 somewhat

reduced; it was suggested by McQuillan to be one of a number of rather

generalised Australian taxa. The pupa has four cremastral hooks and the male

genitalia have socii and a furca (see below). There is a setal comb on the male

third sternite and a hind-tibial hair pencil. This may indicate that the

hypothesis of presence a setal comb being a relatively basal feature in the

ennomine phylogeny and subsequent loss being the derived state is correct.

Consistent absence of a setal comb throughout a tribe, perhaps

associated with loss of a tibial hair pencil, might serve to unite a number of

robust-bodied tribes around the Ennomini, including here the Hypochrosini and

Scardamiini. These share with the Epionini extension and looping of the vinculum

to support lateral coremata. Other tribes recognised in the Palaearctic and N.

American faunas may associate with such a group, such as the Angeronini,

Colotoini, Crocallini and Seleniini.

Many of these groups have a strong furca arising between the bases of

the valves in the male genitalia, but a similar feature is seen in Ourapterygini

where a setal comb is present, and some Boarmiini. Anellar processes, or

processes from the juxta, probably not homologous with the furca in these

tribes, occur in the Lithinini and Nacophorini.

Presence of socii associated with the uncus is probably a primitive

feature as they also occur in Geometrinae. In the Ennominae they are much

reduced or absent in the 'bifid cremaster' group of tribes and also the Abraxini, Thinopterygini and

Gonodontini.

In the female genitalia a single, often mushroom-shaped, usually spined

or dentate signum is more or less general to the subfamily (Fig 2). It is

modified into a ridged structure in Lithinini. More general scobination with no

signum is seen in the Plutodini and the Campaeini (or Metrocampini).

Larvae

Study of the larvae of Ennominae has probably not yet been comprehensive

enough to provide any clear pointers to higher classification. Sato (1984a)

suggested that presence of four external setae on the A6 proleg was apomorphic

for his Hypomecis group, but this characteristic was regarded as

diagnostic for the subfamily relative to Geometrinae by Singh (1953), though not

exclusive to it, and is a feature of the putative primitive ennomine genus Mnesampela

(McQuillan,1985). In Geometrinae the proleg has three external setae.

Dugdale (1961) compared New Zealand ennomine larvae with published

accounts from the Nearctic (earlier papers by McGuffin) and India (Singh, 1953).

He identified four characteristics common to ennomines treated in these works

and possibly diagnostic: (1) anal shield with seta SD1 anterior to seta D1; (2)

hypoproct produced to a fine point, strongly developed; (3) four to eight

annulets (transverse sclerotised bands that are muscle attachments) on A1 -5;

(4) SV group tri- (to 6) setose on A2-5 (cf. bisetose).

Heitzman (1985) performed cladistic analyses on 70 larval characters for

genera of Nearctic Ennomini and related tribes. He found no apomorphies for the

Ennominae as a whole but defined the Ennomini (including the Cingiliini and the

N. American concept of Ourapterygini) on possession of the V2 primary seta. He

noted more than four external SV setae on the A6 proleg in Angeronini,

Epirranthini and Seleniini as well as in the groups referred to below.

Heitzman (1985) and Poole (1987) indicated that the Azelinini (Pero

Herrich-Schäffer) and Nacophorini shared a unique arrangement of multiple

setae on the proleg on A6 (he illustrated 16 setae). Singh recorded up to 16

setae on the proleg of Odontopera similaria Moore (as Gonodontis) so

the Odontoperini may be related to the other two tribes. The Lithinini appear to

be characterised by the presence of six external setae (Heitzman, 1985; J.

Weintraub, pers. comm.)

The Scardamiini and Hypochrosini studied by Singh had five external

setae on the proleg, support for the relationship of these groups suggested

above from consideration of the vinculum modification. Five external setae are

found also in the larva of Traminda Warren in the Sterrhinae (Singh). The

group of genera including Anagoga indicated by Heitzman to be closely

related are referable to Hypochrosini. His other anagogine genera may be

misplaced.

Eggs

Salkeld (1983) surveyed the eggs of Canadian Geometridae. Amongst the 'bifid cremaster' grouping, particularly the Boarmiini sensu lato, there

is a tendency for the walls of the polygonal cells ornamenting the surface to be

heavy and for the cells to be aligned in longitudinal rows. In the putative

Cassymini ('Abraxini') the wavy polygonal cell walls are overlain by a

prominent reticulum, reminiscent of some Larentiinae. The Macariini appear to be

a homogeneous group, with eggs of a rugged appearance, the polygonal cells with

broad and elevated walls, sometimes enhanced by large, domed aeropyles at the

wall junction and a roughly pitted texture to the chorion.

A columnar arrangement of polygonal cells, leading to the walls

separating adjacent rows forming longitudinal ridges is seen in Lithinini and

Caberini. In the former the eggs are not attached to the substrate.

A thick rolled collar encircling the anterior pole is recorded from

several genera in the Ennomini, Hypochrosini (as Anagogini) and Ourapterygini

(including Cingiliini).

Conclusions

The features of adults and early stages just discussed suggest

phylogenetic relationships amongst ennomine tribes somewhat different to those

suggested by McGuffin (1987). His basal groups can be brought together if the

bifid cremaster is considered derived, supported by fovea and valve cucullus

features, as well as loss of socii. This would include a broad concept of

Boarmiini (embracing Bistonini and probably Melanolophiini) together with

Macariini, Cassymini (his Abraxini) and Eutoeini (an Old World group defined

here). True Abraxini and Gonodontini may be related to that group (absence of

socii), and Thinopterygini can also be tentatively placed here, though the setal

comb has been lost.

Loss of setal comb, presence of a strong furca and occurrence of

collared eggs could bring together Hypochrosini (Anagogini), Scardamiini,

Epionini and perhaps Ennomini, Angeronini, other small Holarctic tribes, with

Ourapterygini (+ Cingiliini) also associated though a setal comb is present. The

first two tribes group on larval characters, and the others also share

possession of additional SV setae on the A6 proleg, a feature developed to an

extreme in the next group.

The Nacophorini, Azelinini and Odontoperini appear to form a group on

the basis of larval characters. None is represented in Borneo.

The Lithinini and Caberini may group on features of the egg. The Baptini

and Plutodini appear relatively isolated, though a grouping in the former shows

parallels with the Neotropical Palyadini.

The tribes are therefore treated in the systematic section in the order:

Hypochrosini, Scardamiini, Ourapterygini, Baptini, Plutodini, Lithinini,

Caberini, Thinopterygini, Gonodontini, Abraxini, Cassymini, Eutoeini, Macariini,

Boarmiini (sensu lato). The assignation of genera to these tribes is

based as far as possible on an appreciation of shared, derived features

(synapomorphies): it therefore differs in many respects from the more

traditional arrangement of Inoue (1992).

Host-plant specialisation

The majority of ennomines are arboreal feeders as larvae. Host-plant

specialisation ranges from extreme polyphagy in some tribes to restriction to a

particular plant family in others.

The Hypochrosini are broadly polyphagous but with some specialisation at a

generic level, e.g. Heterolocha Lederer on Caprifoliaceae and the

sister-genera Fascellina Walker and Corymica Walker on Lauraceae

and Illiciaceae. The few records for Achrosis Guenée are from the

Rubiaceae.

The Scardamiini show some association with Flacourtiaceae.

The Ourapterygini are polyphagous.

In the Baptini, the typical genus Lomographa Hübner is a Rosaceae

feeder, but the complex of genera making up the majority of the Bornean fauna in

the tribe is associated with the Aquifoliaceae and, in one instance, the

Flacourtiaceae. There are some records from Piper (Piperaceae).

No records for the Plutodini have been located.

The Lithinini are fern specialists. Indeed, Entomopteryx Guenée was

associated tentatively with the tribe on the basis of adult morphology in an

early draft of the text, the placement has been supported by biological

information discovered between then and going to press (See

Lithinini et seq.).

The Caberini are strongly associated with the Rhamnaceae, apart from the

type genus which feeds on Betulaceae and Salicaceae.

The only records for the Thinopterygini are from Vitaceae.

The Gonodontini and Abraxini are polyphagous.

Some Cassymini genera show preference for Leguminosae, but there is one record

from Guttiferae. Possible Palaearctic representatives are more polyphagous.

The few records for the Eutoeini suggest a preference for Melastomataceae.

The Macariini as a whole are polyphagous, with some temperate groups specialist

on conifers, but the tropical representatives show a strong preference for

Leguminosae.

The Boarmiini include some highly polyphagous genera but also a number that are

much more narrowly specialised. Milionia Walker is only recorded from

conifers, particularly southern hemisphere genera such as Araucaria,

Dacrydium and Podocarpus. Several genera show some preference for the

Lauraceae, such as Racotis Moore, Xandrames Moore, Amblychia Guenée

and the related pair, Krananda Moore and Zanclopera Warren. Racotis

has been recorded from the Annonaceae and Amblychia from the

Illiciaceae (also Pogonopygia Warren), families distantly related to the

Lauraceae within the Magnoliidae. Two genera, Amraica Moore and Microcalicha

Sato, are associated with the Celastraceae.

Ecology and geography

The Ennominae are probably the most diverse and generally distributed of the

geometrid subfamilies. The Geometrinae have a strong tropical focus, whereas the

Larentiinae are more diverse in temperate latitudes and at high altitudes in the

tropics (Holloway, 1986, 1993). In Borneo the greatest diversity of ennomines is

in the lower montane zone at around 1000m where an association of species

specific to that zone overlaps with the upper reaches of the lowland forest

fauna and the lower reaches of an upper montane zone fauna. The Ennominae are

particularly strongly represented within this lower montane association.

The subfamily also has a higher incidence of specificity to particular types of

lowland forest, such as kerangas (heath) forest types or that on limestone.

Examples of the former include Achrosis longifurca sp. n., Achrosis

kerangatis sp. n., Synegia botydaria Guenée, Synegia eumeleata Walker,

Bulonga schistacearia Walker, Peratophyga sobrina Prout (also

montane forests), Sundagrapha lepidata Prout and Diplurodes kerangatis

sp. n.

Limestone specialism is exemplified by Achrosis calcicola sp. n., and Achrosis

alienata Walker.

There are two definite mangrove specialists: Gonodontis clelia Cramer and

Cleora injectaria Walker.

Whilst there are no purely open habitat species, there are a number that

respond positively to forest disturbance and are probably associated with plant

taxa characteristic of regenerating forest. Hypochrosis binexata Walker, Hypochrosis

pyrrhophaeata Walker, Bracca georgiata Walker and Craspedosis

arycandata Guenée were identified as such by Holloway, Kirk-Spriggs &

Chey (1992), and some Cleora Curtis, Hyposidra Guenée and Godonela

Boisduval species may fall into this category too.

Just over 40% of the species are characteristic of the lowlands, and just under

40% are montane, with the remainder being recorded over a wide altitude range.

About a quarter of the lowland species are endemic whereas this proportion

increases to a half for montane species, the overall proportion of endemics

being 30%. A third of all ennomines consists of species restricted to land on

the Sunda Shelf with a further 6% extending from Sundaland to the Philippines or

Sulawesi. About a quarter are more widely distributed in the Oriental tropics.

Only about 5% range more widely through the Indo-Australian tropics (over 30% in

the noctuid groups studied in the series to date).

There is some variation in proportion of various ecological and geographic

categories amongst the tribes, and data on this have been published by Holloway

& Barlow (1992). The Cassymini show a higher degree of endemism and

restriction to lowland forest than the other major tribes, with endemism lowest

in the Boarmiini. The Boarmiini and Baptini are more strongly represented in

montane habitats.

Genera endemic to Borneo are few. Two are monobasic: Sundasclelia Gen. n.

and Lampadopteryx Warren. Bornealcis Gen. n. has three

species. Some genera such as Peratophyga Warren have a majority of

species in Borneo.

Further collecting in Sumatra and Peninsular Malaysia is likely to reduce the

proportion of species apparently endemic to Borneo. The faunas of the three

areas are typically very similar, and the collecting activities of the

Heterocera Sumatrana Society have reduced the number of Bornean ‘endemics’

considerably.

Localisation of species within Borneo is uncommon. Two of the Bornealcis species

are restricted to particular mountain ranges, and further examples are found in Milionia

and Dasyboarmia. Abraxas subhyalinata Röber is only known from Pulo

Laut in southern Borneo and in the Lesser Sundas, a distribution type already

noted for some agaristine noctuids (Part 12). Ruttellerona pulverulenta Warren

is known only from Taganak, a small island off the north coast of Borneo, but

has affinities with taxa in Sulawesi and further east. This is a pattern seen in

some butterflies such as Eurema alitha and Cupha arias that just

reach the northern part of Borneo or occur on small offshore islands (e.g. Pulo

Mangalum), but have ranges extending through the Philippines and further east. Pseudeuchromia

maculifera Felder & Rogenhofer is another ennomine of this geographic

type.

Most genera represented in Borneo exhibit their greatest species richness in

Southeast Asia or the eastern Himalayan region, and attenuate in richness

eastwards into the Australasian tropics. A few, however, are more diverse in the

Australasian tropics and attenuate westwards. Bracca Hübner and Craspedosis

Butler reach their most westerly extremity in Sundaland, but Milionia Walker

extends further onto the Asian mainland, reaching Japan.

One species is adventive. Macaria abydata Guenée is a Neotropical

species that has established itself widely round the western Pacific margin

during the past decade and a half, probably with Hawaii as a staging post. Its

spread parallels to some extent that of the Leucaena psyllid (See

Macaria abydata Guenée).

|